The Landscape After the Battle

A year after Alexei Navalny’s death, his movement struggles to redefine itself—fractured, exiled, and estranged from political action. Yet his vision for a democratic Russia endures.

Editor’s Note

Hello! It’s Aron Ouzilevski, DOXA’s newsletter editor, here to bring you all things Russia—in English.

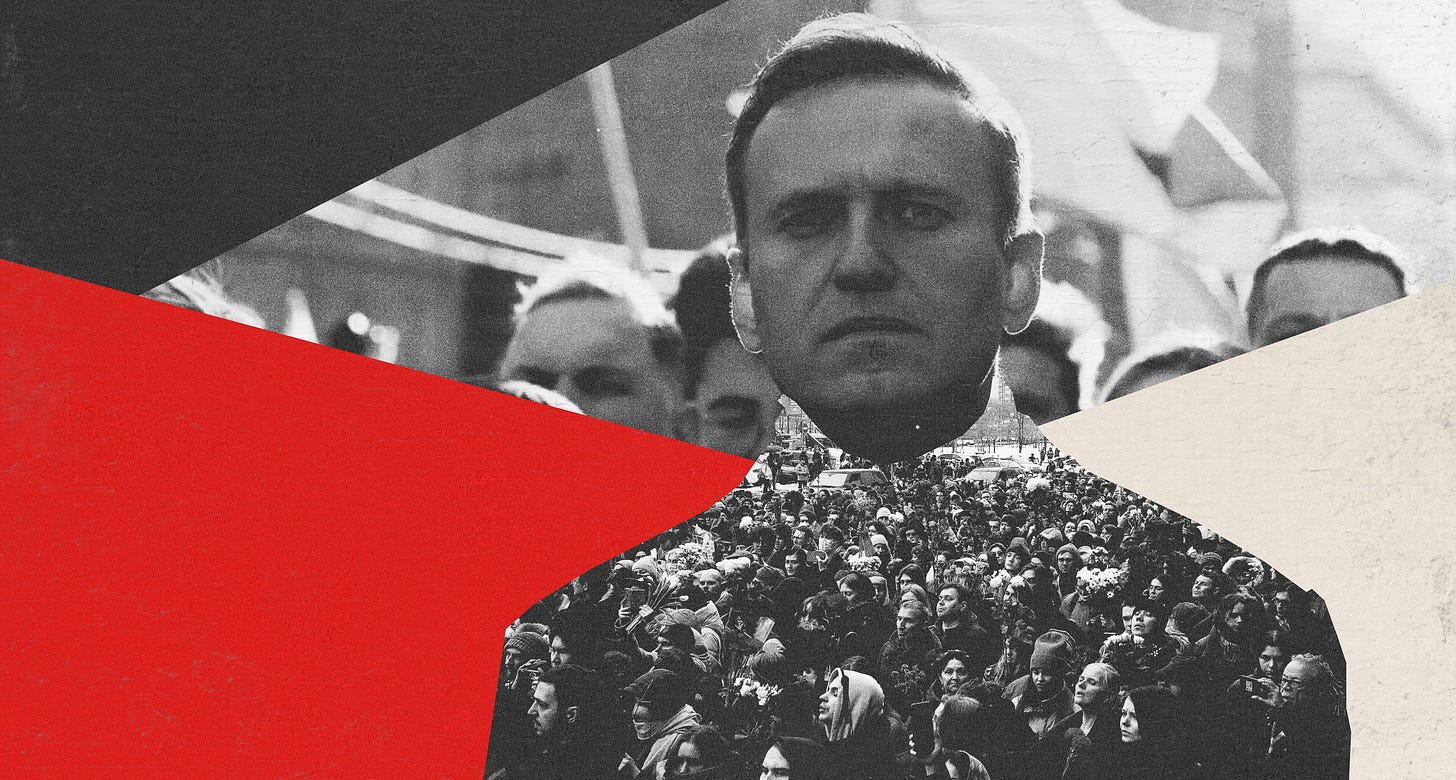

Today marks one year since opposition leader Alexei Navalny died in an Arctic prison colony. Many were moved by the large turnout at his funeral, which followed a nine-day battle with the authorities who refused to release his body to his mother right away. His widow said that the body was kept to remove traces of Novichok poisoning.

Despite the cold winter flurries and restrictions on public gatherings—especially for the funeral of a man the Russian government labeled “extremist”—Navalny's followers lined up for miles in Moscow’s Maryino District, his home for many years. As feminist scholar Natalia Baranova wrote in the first of two pieces we published for this anniversary on Friday: "In a time of extreme repression and bans on public gatherings, such collective action carried real weight."

Out of concern for their own safety, his widow and children—currently in exile—have yet to visit his grave. No investigation into his death was conducted, and the lawyers who defended Navalny are now in prison for “involvement with extremist groups.”

A year later, a new line stretches for hundreds of meters at his grave, where flowers and photographs continue to appear. In cities across Europe, where many Russians have escaped to since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, small memorials and gatherings continue, keeping his memory alive.

But while his charisma and his political platform remain central to his legacy, UC Berkeley visiting scholar Ilya Matveev argues in our second piece marking the anniversary that the new reality of extreme wartime repression and attacks from other opposition groups are critically undermining Navalnism as a political project.

By Ilya Matveev

The first few pages of Alexei Navalny’s memoir Patriot, published posthumously last October, reads like a manuscript from a bygone era. He writes about “Smart Voting,” the strategic voting system he devised to chip away at the Kremlin’s dominance. He recalls his viral anti-corruption investigations, which exposed the lavish lifestyles of Russian elites and aimed to mobilize the public against Putin’s regime.

“We simultaneously entertained and outraged our audience with images of the life led by the ‘humble patriots governing our land’—explaining how the mechanisms of corruption work and calling for practical actions to cause maximum damage to Putin’s system,” Navalny wrote of his team’s YouTube investigations, which garnered tens of millions of views and were watched like episodes of a gripping HBO drama.

Not long ago, opposition politics in Russia still felt possible. We debated Navalny’s work, followed “Smart Voting,” watched his exposés, and took to the streets to back his campaigns.

That world no longer exists.

Even before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Kremlin had begun dismantling Navalny’s movement—imprisoning key members, forcing others into exile, and branding his Anti-Corruption Foundation an extremist organization. Independent media outlets were systematically shut down.

Shortly thereafter, when the Kremlin began its murderous offensive in Ukraine, the space for non-clandestine activities in Russia disappeared entirely. A brazen attempt on Navalny’s life in 2020, which he describes so strikingly in his memoir, was a major first step towards eliminating the last vestiges of pluralism in Russia altogether.

Yet, there are still options left for those who remain in Russia and have a sense of civic duty. Such forms of activism are, however, either apolitical (for example, eco-friendly initiatives such as volunteer work cleaning the Kerch Strait) or they are confined to closed spaces and small affinity groups. This is counter to the DNA of the Navalny movement. It was unabashedly political, never afraid of a direct confrontation with the Kremlin. Navalny and his supporters were open about their ultimate goal of democratizing Russia’s political system.

Moreover, it was boldly public, coordinated through popular independent media and open channels. Now operating from exile, Navalnism, kept barely alive by the remaining members of the team, is yet to reinvent itself.

Of the three pillars of Navalnism and Russian opposition politics—media, street protests, and voting—only one remains. Opposition media has reconstituted itself abroad, continuing to inform both Russians inside the country (despite blockages, via VPNs) and the diaspora. But without the other two pillars—street protests and voting—its political influence has waned. The issue isn’t that the opposition media is “divorced from Russian realities,” as some critics claim, simply because it is produced in exile. The real problem is that it is divorced from political action.

Isolated from practical politics, the anti-Kremlin public sphere suffers from constant in-fighting and vitriol. The Navalny team in particular is facing multiple attacks from their supposed allies in the opposition camp. This is due, in part, to the blunders made by the Navalnists themselves such as Leonid Volkov’s attempt to lobby on behalf of Russian oligarchs Mikhail Fridman and Petr Aven who faced Western sanctions (something he later described as a grave mistake).

More importantly, however, the attacks on the Navalny team satisfy the need to find a scapegoat for the opposition movement’s general failure. Since Alexei Navalny was the de facto leader of the Russian opposition, his team is a convenient target for blame and resentment.

Rivals of the Anti-Corruption Foundation exploit these emotions to score political points and keep their audience engaged, deepening the broader crisis of the opposition.

Still, not all is lost for those striving for a free and democratic Russia. Sociological research shows that the Kremlin’s rabid imperialism has not been fully embraced by the population, which remains skeptical of propagandistic claims—such as the idea that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people.” Under-the-radar education, including study groups and online classes, as well as cultural production and activism, continue to persist.

Yet Navalny’s political legacy is in crisis, and we must be honest about that. But part of that legacy was his refusal to cave—to accept his reality. His example gives us strength to keep fighting, to remain determined, to be creative and brave.

A year after his murder, debates about Navalny’s politics have largely died down. This is probably a good thing, since many of the accusations made against him—such as the notion that he supported the annexation of Crimea—were malicious and dishonest.

What remains is the image of a man who certainly made mistakes (notably the nationalist leanings of his early career), but who was quite capable of consciously correcting them. Since the early 2010s, he has decisively distanced himself from Russian nationalism and apologized for some of his earlier words. He was a fierce fighter, a shrewd tactician and a talented, imaginative writer and orator.

Navalny’s memoir will be read and re-read, his videos watched and re-watched. His political platform, based on real patriotism, a commitment to democracy (its formal norms as well as its civic, mobilizational substance) and a sensibility towards social problems will form the basis of Russia’s future reconstruction. It is up to all of us to bring this moment closer.

Ilya Matveev is a political scientist and leftist researcher who was previously based in St. Petersburg. He is now a visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the Public Sociology Laboratory research group.