A Russian High School Student On How the Government Indoctrinates Its Youth

"If you want to get anywhere, you have to accept the patriotic programming."

Editor’s Note:

Hello there! It’s Aron, your weekly newsletter editor with another translation.

This week, we bring you a glimpse into the everyday lives of Russian schoolchildren. In the following interview—conducted by journalist Nina Nevzanova—a high school student from Russia’s Ural region, speaking anonymously via DOXA Journal’s hotline, offers a firsthand account of how state propaganda has permeated nearly every aspect of school life.

Visits from wounded veterans regaling students with stories from the Ukrainian front are becoming routine. Career guidance classes now steer students toward professions in drone production. Excerpts from ultranationalist writers like Zakhar Prilepin appear in standardized reading comprehension tests.

Yet, according to “Feodor,” the teenager at the center of this account, these efforts to instill patriotic values largely fall on deaf ears. Teachers, too, find quiet ways to resist.

The over-ritualized, compulsory nature of these initiatives recalls the late Soviet period, when ideology had become a hollow performance. In place of Kalashnikov assembly courses, students now watch instructional videos on how to build drones.

But the parallel is imperfect. Back then, the ideological fervor was waning. Now, the Kremlin is only beginning its attempt to militarize a generation.

Unlike their late-Soviet predecessors, Russia’s “Generation Z” is also coming of age in a digital world. One moment, they share memes and rainbow flags in private chats; the next, they stand outside in the cold, singing the national anthem.

Interview by Nina Nevzanova

Translated by Aron Ouzilevski

“I don’t think you fully understand what’s really happening in Russian schools, so let me explain,” Fedor—a queer-identifying high school student from Russia’s Ural region, whose name has been changed for security reasons—responded to our first interview question.

DOXA Journal has extensively covered how Russian schools are transforming since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. We’ve written about how questions about the war in Ukraine now appear in standardized tests, how plaques—commemorating veterans of the war—now hang in school hallways, and how schoolchildren are being taught how to operate drones.

But how are these changes felt on the inside?

“Wherever you turn—they’re always there”; How “The Movement of the First” seeps into school classrooms and events.

Nina: In your call to the DOXA hotline, you specifically highlighted the “Movement of the First,” Why?

(The Movement of the First was founded in July 2022—one of many patriotic initiatives that emerged in Russia since the start of the full-scale invasion—with a mission of supporting education, career development, and leisure activities for children, while promoting a worldview rooted in “traditional Russian spiritual and moral values.” In September of that year, Vladimir Putin ordered the government to allocate more than 21 billion rubles [240 million USD] annually to the group. In 2024, he appointed a veteran of Russia’s war in Ukraine as the organization’s leader.

Feodor: Because no matter where you turn, they’re everywhere. It’s a platform that has consolidated various organizations, like the “Russian Movement of Schoolchildren” and “Yunarmiya”—a modern version of the Soviet-era Pioneer movement. In 2022, when it was first established, you could still attend extracurricular clubs in school without joining this movement. But now, even to sign up for a theater class, you have to register with the movement.

All the active young people—who are, for the most part, good kids—end up in the “Movement of the First.” And the government then tries to indoctrinate them. If you look at the social media page of any active student, you’ll likely see posts about their involvement in the movement. In theory, it’s not a bad thing to get kids involved in school life. But there’s little tangible value to this movement—they’re not even getting kids to do community service.

Nina: So you weren’t able to avoid it yourself?

Feodor: No way. It’s like the Hitler Youth in Nazi Germany.

If you believe the website, the movement already has ten million members—more than half of all of Russia’s schoolchildren [18 million]. It’s all just numbers to fill a quota. This especially feels obvious when representatives visit classrooms and urge students to join while saying, “We won’t force you to participate in anything, just register on the platform.” That’s when I began to doubt this whole thing, and it explains the inflated numbers. The real number of active members is probably closer to one million.

(Editor’s note: The emphasis on inflated membership figures seems to reflect a broader pattern in modern Russia, where bureaucratic targets and quotas often take precedence over genuine participation. As with other state-backed initiatives, enrollment numbers serve more as a metric of compliance within the chain of command than an indicator of actual engagement.)

Nina: And they really don’t force you to take part in anything?

Feodor: For now, yes. You can just register and forget about it.

Nina: What do your classmates think about this?

Feodor: Many of my classmates have their own personal Telegram channels that are like typical teenage diaries. They’ll make jokes about how this is just like a summer at a Soviet pioneer camp, share rainbow flag emojis, complain about nationwide bans… And the next morning they go to school to take part in the “Movement of the First,” where they are forced to condemn the types of things they shared on their Telegram.

It's like there’s a case of mass, collective Stockholm syndrome.

The same goes for Ekaterina Mizulina (a politician and pro-Kremlin influencer, who advocates for censorship and supports designating the LGBTQ+ movement extremist. Despite her extreme pro-Kremlin views, she maintains steady popularity among young Russians).

She might get a popular rapper banned (Mizulina is notorious for her denunciations of cultural figures), yet kids will still admire her, and ask her to lobby for improvements in their school.

Nina: Did you find anything useful in the “Movement of the First” for yourself?

Feodor: Well, I liked a few journalism lessons, for example. But one lesson, which thankfully occurred when I was sick and couldn’t go—focused on how to verify information and spot fake news. Right away, the instructors said, “Trust only RIA Novosti (Russia’s major state-run news agency, notorious for spreading disinformation).” Why do kids need that? They just sit there on their phones during this nonsense [the lesson].

“Instead of Russian lessons, we get veterans”; How patriotic events are now overwhelming school programming.

Nina: They probably just sit on their phones during Conversations About Important Things, too.

Feodor: It didn’t stop with Conversations About Important Things (a state-mandated patriotic lesson series that began after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine). Now, they use other subjects to promote patriotism. For example, the standard emergency preparedness class was renamed Fundamentals of Security and Defense of the Motherland. In my brother’s class, they once just played a 40-minute video of tanks with some epic music over it. Madness.

They also wanted to introduce Family Studies (a subject proposed for the school curriculum in 2024 aimed at instilling “pro-family values and meanings,” including marriage, childbearing, and chastity), but my school didn’t implement it. In general, Conversations About Important Things can be taught in different ways—technically, you could even discuss something positive. But most of the time, teachers just read from official guidelines. It looks really strange.

Imagine this: the same people who teach Russian literature and math suddenly start lecturing students about warships. It’s bizarre.

Nina: Do veterans of Russia’s war in Ukraine come to school often?

Feodor: Yes—and they’re not very subtle. One veteran once said out loud how they “captured Mariupol.” Sounds to me like a bit of a slip-up. Weren’t they supposed to have “liberated” it, and not “captured” it?

Another time, a really bulky man came in. I asked him a lot of questions—like whether he had seen the RDK (Russian Volunteer Corps, a paramilitary unit made up of anti-Kremlin Russian fighters aligned with Ukraine) or the Freedom of Russia Legion (a military unit composed of Russian defectors fighting against Putin’s regime).

Feodor: Did you get in trouble for asking that?

Nina: No, I played it smart. I started off with something harmless, like, “Oh, how can we support you?” Basically, I acted like a model Hitler Youth member to get the answers I wanted.

My classmates asked a lot of questions, too. I don’t think it’s because anyone told them to—they were just genuinely curious. Boys are into this stuff: fights, weapons…

By the way, it’s not just veterans from the war in Ukraine who come to speak at our school. We also get other veterans—mostly labor veterans, Afghan war veterans… And every time, they recite the same exact poem about the Anglo-Saxons. I’m not joking. It’s surreal. The poem ends with a line like, “Let’s kill the stupid Anglo-Saxons,” or something along those lines.

(Editor’s note: In Russian nationalist rhetoric, “Anglo-Saxons” is often used as a catch-all term for Western countries, particularly the U.S. and U.K., portraying them as hostile forces behind global conflicts and anti-Russian policies.)

Nina: How did your classmates react to the speeches about the Anglo-Saxons?

Feodor: They listened. Some of them even put their phones away. The only real complaint was that instead of preparing us for our Russian exam, they were bringing in veterans.

Nina: So does that mean you’re alone in your anti-war stance?

Feodor: I have a teacher who once made a very subtle dig at everything happening. When she wrote the Latin letter “Z” (a pro-invasion symbol in Russia) on the board, she added an extra stroke through the middle. Everyone started joking, asking, “Why are you writing it like that?” She just shrugged and said it was for political reasons. You get the idea.

(Editor’s note: The implication is that the teacher used the letter for educational purposes but altered it as a quiet act of protest.)

She’s a good person, though not the best math teacher. She treats me well. Honestly, every anti-regime person I’ve met has been kind of odd. Obviously, there are plenty of people who are against all this, but they don’t really feel like my people. And some of them joke about the war in such a weird way. There are so many memes now.

Feodor: Maybe humor is a coping mechanism for everything that’s happening?

Nina: My classmate’s dad is in Ukraine fighting. My teacher’s brother died in the war. Turning it into a joke doesn’t feel right. Drones are already reaching us, and they’re still laughing.

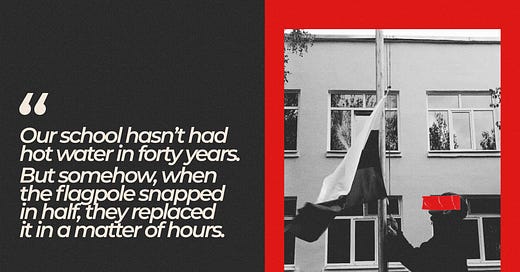

That reminds me of something. A month ago, a truck crashed into our school flagpole where the Russian flag was hanging. The pole snapped in half. I came in the next day, and there was already a new flagpole. Meanwhile, our school hasn’t had hot water in forty years. But somehow, they replaced the flagpole in a matter of hours.

This is dystopian. By the way, I’m writing a book in this genre right now. It’s going to be set in a post-apocalyptic world following a nuclear holocaust, where another dictator emerges. Something about the cyclicality of history.

“Dudes are grabbing each other”; About the queer experience in school and LGBTQ+ propaganda.

Nina: In your message to the DOXA hotline, you said you identify as queer. Do people at school know?

Feodor: What even is queer? I mean, snails are queer—they don’t have a sex... Anyway, I identify as queer, or asexual. People at school don’t really know. Honestly, when I transferred to this school and saw how the boys here were grabbing each other, it felt strange.

I don’t even know how to describe it. I mean, my classmates are xenophobes, fascists, they jokingly quote Mein Kampf—and at the same time, they do stuff like this.

Some of my classmates have even confided in me that they’re not straight.

Nina: Does your school hold any events against so-called “LGBT propaganda”?

Feodor: In elementary school, there wasn’t anything like that, of course. They didn’t talk about homophobia, or far-right patriotism, or the war. In middle school, they might have dropped a little hint. In high school, they speak more critically of LGBTQ+. But I haven’t heard outright calls for violence against LGBTQ+ people.

Mostly, they push the war narrative—asking students to write letters to soldiers, send them care packages. They even hold these kinds of events for adults—it’s propaganda for every generation. I try to avoid taking part in it.

(Watch: DOXA’s video team analyzes military propaganda in Russia’s schools.)

Nina: Can you escape it?

Feodor: You can always find a way. The key is to spend ten minutes explaining why you can’t participate—say you’re not feeling well, for example—and they’ll leave you alone. But you can’t get out of everything.

Like with our theater club. We have a small troupe, and we wanted to put on an ordinary play. Right away the school administrators told us to make it patriotic. I won’t argue—there are plenty of great works about the Great Patriotic War (the Russian term for World War II). But not for kids who are just acting for the first time.

At first, we tried suggesting something else, but in the end, we gave in. It’s the same with registering for The Movement of the First. If you want to participate in any extracurricular activities, you have to accept that at some point, you’ll be immersed in this patriotism. And that’s bad for kids. They hear about patriotism everywhere, but they don’t actually feel it.

Just yesterday, we had our final oral exam before the standardized test, and every single topic was patriotic. It’s hard for students to talk about these things—they’re just kids; they don’t fully understand what it all means. But the test materials are packed with texts by Zakhar Prilepin.

(Editor’s note: Zakhar Prilepin is a nationalist, ultraconservative Russian writer and politician who has been involved in the war in Ukraine since before the full-scale invasion. His works often glorify Russia’s imperial ambitions, depicting armed conflict as both righteous and inevitable. In May 2023, he survived an assassination attempt.)

Every Monday, we have to stand in the school yard while the Russian national anthem plays. There are so many students that not everyone fits in the yard, so the rest just stand by the windows and watch. Just picture this: some guys march with the flag, students stand in the freezing cold, watching, and the others are stuck inside, unable to hear a thing.

So we just stand there in silence for six minutes, sometimes whispering, “Has the anthem ended yet?” It’s surreal.

Nina: How do you see your future in the midst of all this surrealism?

Feodor: I’d like to get into the Higher School of Economics (a prestigious university that has branches across Russia’s major cities). I’d like to study something related to the creative industries, and maybe get into filmmaking.

Nina: Aren’t you worried you’ll have to take part in patriotic initiatives? There’s a lot of that in the creative industries now.

(Editor’s note: Censorship and wartime propaganda have severely restricted free expression in Russia in recent years. The Ministry of Culture frequently funds state-backed war films and anti-Western spy thrillers.)

Feodor: Yeah, it’s a complete mess. I hope I can take something good from each organization and avoid the rest. But in film, things will only get worse over time. It’ll either be folklore—movies about Leshy (a Slavic forest spirit) and Maslenitsa (a traditional holiday)—or patriotism.

Nina: You mentioned that you liked the journalism training sessions in the “Movement of the First.” Have you considered becoming a journalist?

Feodor: No. How could I be a journalist? What would I even be able to report on in today’s Russia? Even as a filmmaker, I won’t be able to express myself, at least for the foreseeable future. But one day, the sun will rise.

By the way, we now have career guidance classes. A good initiative, but the problem is that they only talk about professions the state needs—technical fields, working with drones. I’ve never seen anything humanities-related there. And half our class is made up of students who want to study the humanities.

Nina: What do you think about drones being discussed in schools?

Feodor: Well, they’re not only used for military purposes. But in general, I’m a pacifist. I plan to refuse military service. As long as I have the option, I’ll go to hospitals and get medical exemptions (a common way young men in Russia try to avoid mandatory military conscription by obtaining official diagnoses or disabilities that make them unfit for service).

Nina: Have you thought about leaving Russia?

Feodor: A year ago, I did. Especially since my mom had an opportunity to move us to another country. But now, neither I nor my parents want to leave. This is our country, our homeland. By the way, where do you live?

Nina: Not in Russia.

Feodor: Where exactly? I probably sound like an officer from Center “E” right now. (Center “E,” short for the Center for Combating Extremism, is a unit of the Russian police known for monitoring dissent and political activism.) Actually, an “Eshnik” (slang for an officer from Center “E”) once messaged me. I had left a comment about Navalny’s death in a Telegram chat. After that, someone sent me a private message: “Hey, are you Feodor?” I freaked out and deleted the conversation.

Nina: I get it. Maybe life would be easier if you were an activist in the “Movement of the First,” instead.

Feodor: And then I’d be left struggling to make sense of it all once the tyranny ends.

Nina: Maybe the people who joined voluntarily won’t struggle at all.

Feodor: Oh, I hope they do.

Fascinating interview. Many thanks.